Enduring Traces of Coloniality in Prague’s Public Space

BY KACPER DZIEKAN (Affiliate - National Heritage and Traumatic Memory Cluster)

September 5, 2025

Photos by: Erica Lehrer

On one hot July morning, Prof. Markéta Křížová of Charles University led a group of TTTM’s National Heritage and Traumatic Memory (NHTM) research cluster members – gathered in the Czech capital to participate in the Memory Studies Association’s Annual Conference – through the streets and alleys of Prague, highlighting for us visible, if not , traces of the city’s implication in colonial histories. The walking tour formed the core of our cluster’s annual retreat, but it was also a much-needed exercise after the 5 intense days of panels, roundtables, and plenary sessions, all indoors. Strolling around back streets and bridges of Prague’s historic heart, Markéta pointed out various figures illuminated by the sun’s summer rays. Representing noblemen and Jesuit priests, some of them closely linked to Czech culture and history, with the latter particularly involved the ‘civilizational mission’ of spreading Christianity across the world – a key pillar of European colonial ideology.

Walking tours with an emphasis on the colonial past and decolonial initiatives have increasingly become a popular cultural practice in European cities such as Berlin, Lisbon, London, and Paris. They offer a confrontation with painful historical legacies and serve as an educational tool to raise awareness among both residents and visitors. But how are such tours relevant in countries (both those in East Central Europe, but also for example Switzerland) that never had colonies? Markéta’s tour showed clearly how colonial entanglements stretch far beyond direct overseas territorial holdings, leaving marks also in the cities of less dominant, but no less implicated, actors.

Photos by: Erica Lehrer

Such is the case of Prague, the capital of Czech Republic. Long behind the Iron Curtain, today the city is awash with international travelers seeking a slightly “different” Europe. It appeals to seekers of literary genius such as Franz Kafka or Bohumil Hrabal, and the city’s romanticized image stretches back in time to the era of the Habsburg Empire, or further still to the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. Prague’s entanglement with colonialism could begin here. During the reign of the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II in the 16th and 17th centuries, Prague became the capital of his empire. Rudolf’s legacy – and the ongoing territorial, cultural, and religious expansion of European empires – left innumerable traces in today’s cityscape, even if direct colonial endeavors were seemingly far away.

Fairgrounds near the Vltava river, once the site of a “human zoo”. Photo by: Erica Lehrer.

Colonial traces can also take invisible forms, in what NHTM member Roma Sendyka calls ‘non-sites of memory’, pointing to the locations of events, phenomena, or simply moments in history that the dominant culture would rather forget about or simply pretend never happened. In Prague, this is the case with the infamous so-called “human zoo”. Throughout the late 19th and early 20th century, rulers of various European countries offered their residents a dubious form of entertainment by exhibiting human beings of non-European origin. The legacy of these racist, pseudoscientific forms of colonial violence poses challenges to today’s local authorities, museums, universities, and other cultural actors. In some cities that were central to imperial, colonial activities (e.g. Berlin or Lisbon) sites of such “zoos” are beginning to be critically examined, formally marked, and even intervened in with community-led exhibitions. But countries that do not carry the burden of direct colonialism, and those without large or empowered minoritized populations, tend not to perceive such histories as their own, nor in need of confrontation. If not for Markéta’s pointing out the location of a grassy clearing on the bank of the Vltava river – a site still today hosting fairgrounds with snack booths, visible from the Lesser Town side of the Mánes Bridge – one would never imagine that a “human zoo” showcasing African, Inuit, and Haudenosaunee peoples had titillated the city’s former inhabitants. As Markéta stressed, a commemorative plaque would shed light on the issue to unaware passers-by, but such an intervention is impossible in the current political climate.

Photo by: Erica Lehrer

Such oblivion is not unique to the Czech case, but can be observed across East-Central and South-Eastern Europe, countries that do not fit neatly into the binary division of Global North and Global South that so commonly determines the decolonial and postcolonial debate. As Jie-Hyun Lim argues, such societies might be better positioned as belonging to the “Global East(s)”. Here, collections and narratives presented in local Ethnographic or Archeological museums are seldom updated, or lack critical approaches or shared ownership with source communities – a regional oversight discussed by NHTM members Erica Lehrer and Joanna Wawrzyniak, and the subject of their forthcoming edited volume Decolonial Museology Recentered: Thinking Theory and Practice Through East-Central Europe (DeGruyter, 2026). There are, however, a growing number of curatorial interventions and fresh temporary exhibitions that are beginning to break out of the traditional pattern. During our walking tour we visited the Náprstek Museum of Asian, African and American Cultures. While there is room for improvement regarding the Museum’s permanent exhibition, a temporary one reflecting on the Czech Republic’s Vietnamese diaspora and co-curated by its members offered a fresh look at this community with accessible, personal stories.

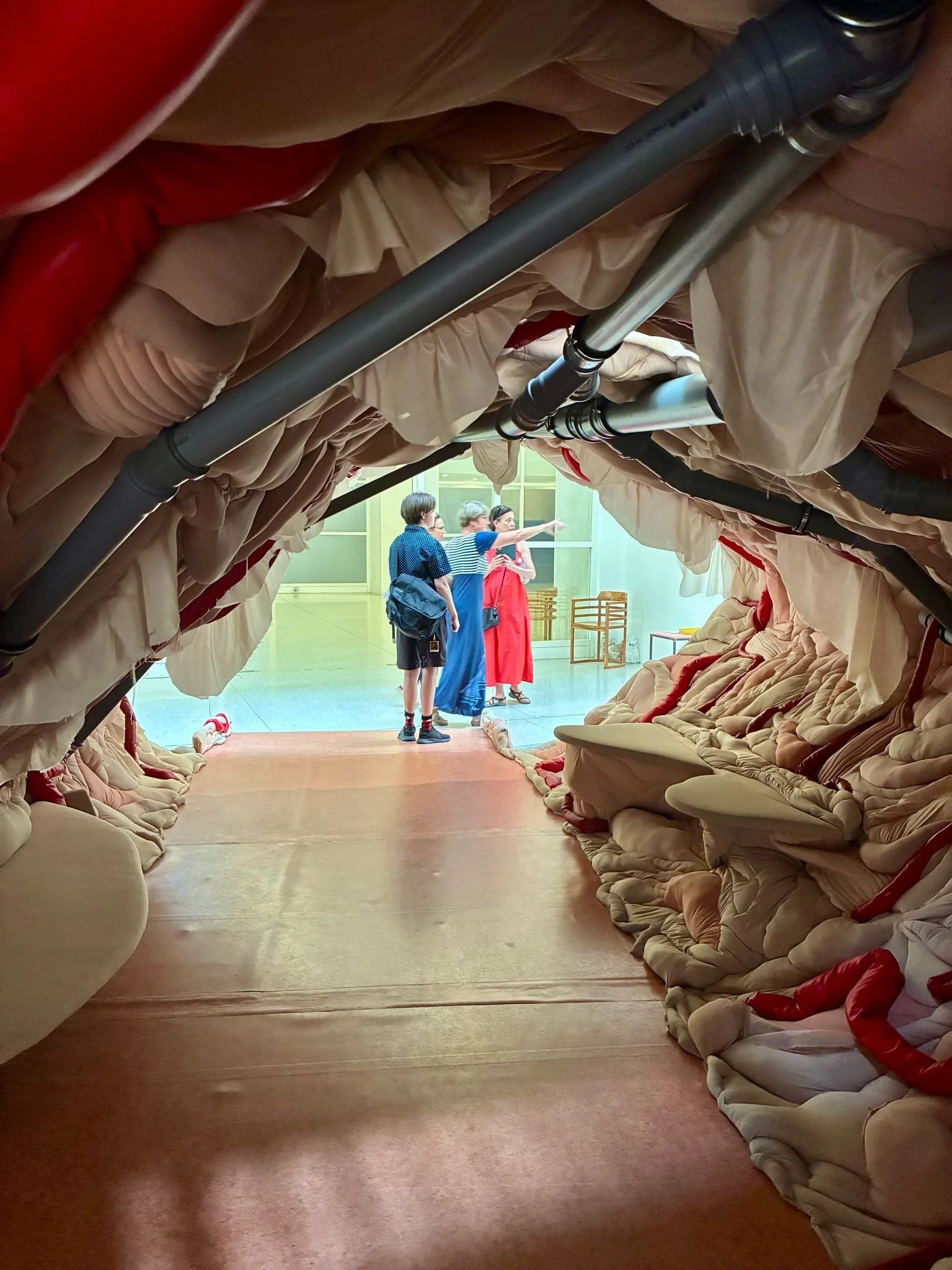

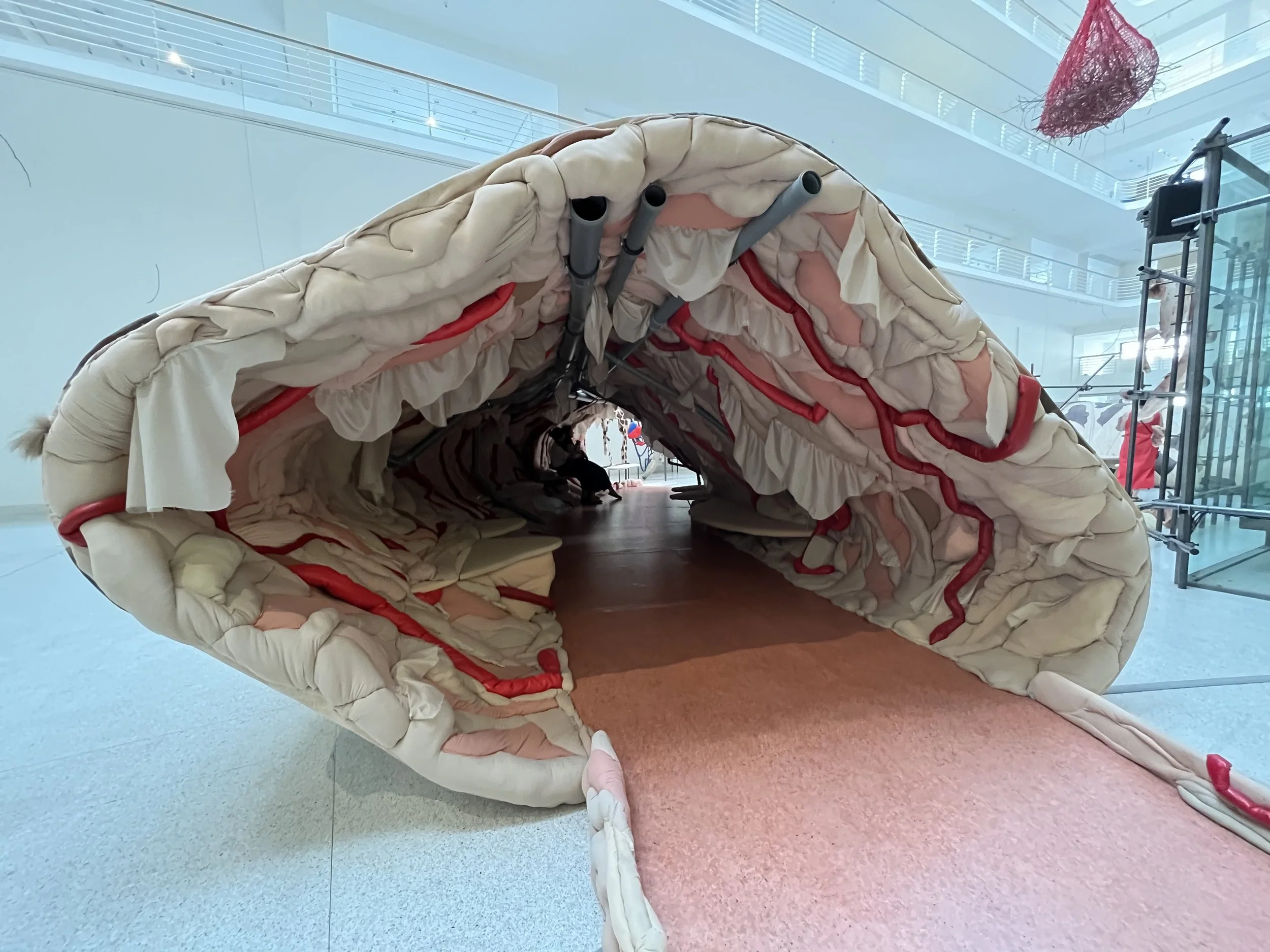

We also had a chance to view another exhibition dealing with coloniality, Eva Koťátková’s The heart of a giraffe in captivity is twelve kilos lighter. The artist’s intervention – a huge, deconstructed giraffe splayed across the immense gallery with bodily orifices that visitors could enter and contemplate – had been commissioned for the Czech and Slovak Pavillon at the Venice Biennale in 2024 and is currently on display at the National Gallery’s Trade Fair Palace. Inspired by the history of Lenka, a giraffe brought to Czechoslovakia in 1954 from Kenya, who died at the Prague Zoo only two years later. The artist poses uncomfortable questions about the long shadow of colonialism and its legacies. Showing this work on the premises of the National Gallery sparked controversy and attracted protests in front of the building.

Sadly, this experience is sobering evidence that decolonizing East-Central European museums remains a distant horizon – and ongoing change means decolonization itself is an open-ended project. Nevertheless, calling attention to colonial legacies such as the story of Lenka or the site of the “human zoo” generates awareness and spurs public debate. Even if it is accompanied by backlash and a general lack of comprehension among many local inhabitants, such steps can lead to broader, more structural changes. Activist academics like Markéta step beyond the standard comfort zone of research and observation, as taking a stance and advocating for the necessity of facing difficult truths makes one vulnerable, and even risks having one’s credentials questioned. Yet perhaps this is the price of dedicating oneself to true social change?