Museums, Authority, and the Ambivalent Status of Public Statements

BY HUGO RUEDA (Affiliate - National Heritage and Traumatic Memory Cluster)

May 2, 2025

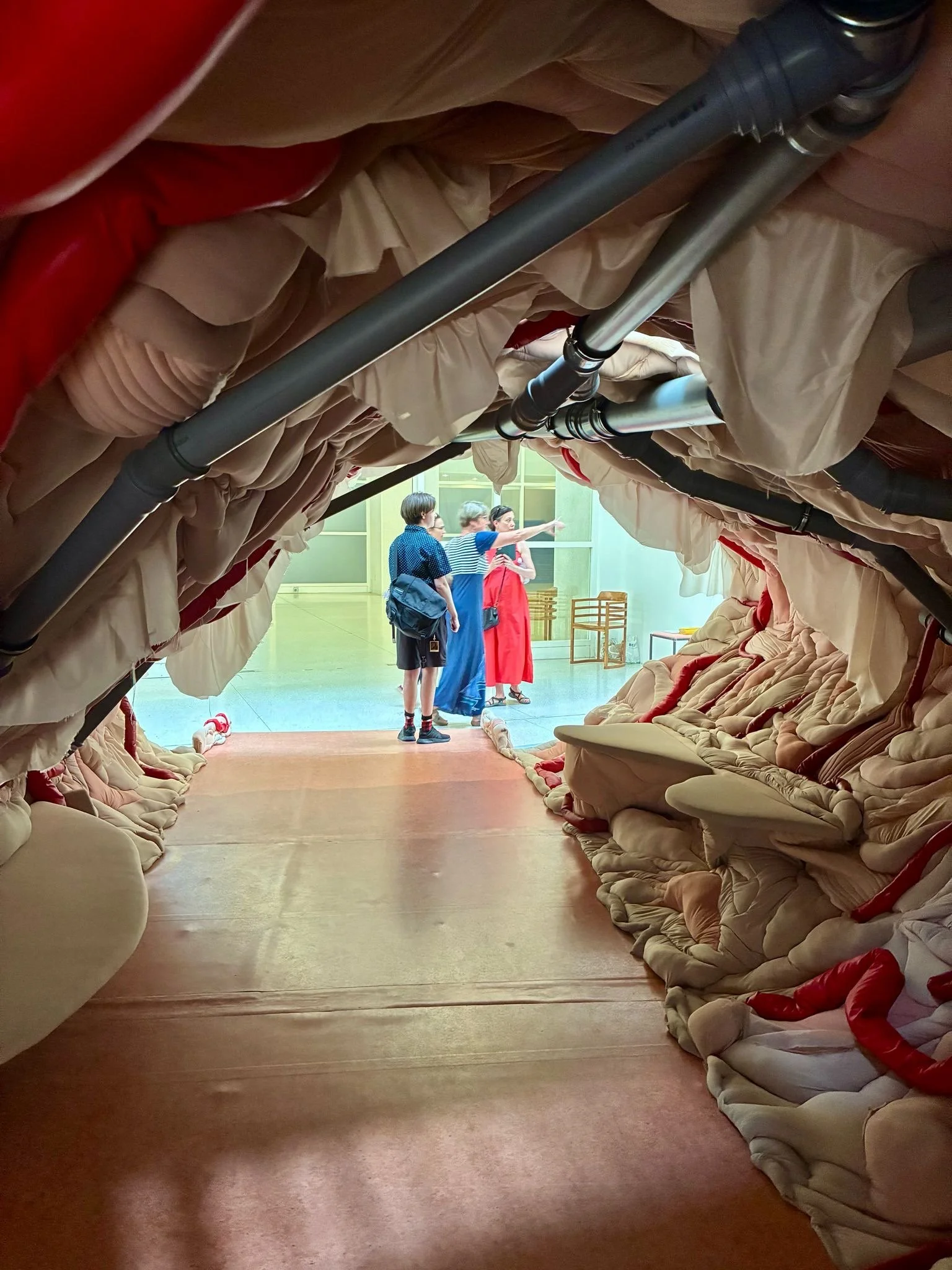

TTTM Team on the first day of the Annual Meeting at the Ottawa Art Gallery. Cara Tierney’s “they” is in the background. Photo by: Katrina Hermann.

The panel “Museum Statements, Open Letters, and Institutional Critique in Times of Polycrisis”, held during TTTM’s annual gathering in Ottawa in October 2024, brought together eight speakers – a mix of scholars and practitioners – who accepted the call from Co-Investigator Dr. Shelly Ruth Buttler and Research Assistant and PhD student Varda Nisar to explore the politics of museum statements and open letters in the face of current conflicts, for example those related to the 2020 assassination of George Floyd and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, the climate crisis, and the ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people in Gaza. The organizers encouraged speakers to frame their contributions in relation to a list of guiding questions that spanned ethical, political, institutional, and affective dimensions. The first of these questions set the tone for the panel, subsequent discussions of it, and the present reflection: “Are public statements by museums useful?”

The question isn’t new to me, it’s been buzzing around in my mind for a while. As both a museum consumer and practitioner—I worked at the National History Museum of Chile for five years and currently work with the Maude Abbott Medical Museum in Montréal—I am quite familiar with the genre. I’ve never written a museum statement, nor have I formally requested one from an institution. Nonetheless, I’ve read a fair number of them in my inbox and Instagram feed. Sometimes I pause to reflect on their messages; other times I shrug them off as hollow.

And yet, the fact that museums continue to issue statements suggests that someone must find them useful. Museums’ decision-makers must believe that public statements serve a purpose – they proclaim to be in support of one or another embattled community – otherwise, the exercise would be futile. But what if museum statements are not for the public at all? What if they are primarily useful for museums themselves? This is why, rather than ask Are public statements by museums useful? my contribution to the debate is to reframe the question as: to whom are such statements useful?

This shift uncovers tensions between the public’s unacknowledged expectations regarding museums’ authority, and their supposed (and often self-claimed) neutrality. Authority is a tricky concept. It combines two key ideas: expertise, and the right to rule and make decisions. Indeed, the word “authority” shares its origin with the word "author” (from the French autor, meaning creator). In museums, these meanings converge strongly: the knowledge authored by museums is broadly understood by the public as authoritative. If museums hold power, it is precisely because they are sites where knowledge is actively produced, curated, and legitimized.

This connection between “author” and “authority” is at the heart of how museums legitimize the knowledge they produce. Born out of and authorized by European imperial projects, museums collected, classified, and displayed “otherness” in the name of progress, defining irreconcilable distances between “us” and “them.” While in recent years many museums have gone to great lengths to present themselves as neutral spaces of learning and reflection, their practices remain deeply entangled in a range of biases and political interests. Museums are not, and probably could never be, neutral spaces. As knowledge-producers closely aligned with nations and powerful communities’ elites, they are embedded in specific sociopolitical structures, which undermine their claims to, and even their good-faith efforts at, neutrality.

Public statements, by extension, are not neutral acts of concern for the well-being of humanity. I see them more as evidence of museums’ enduring historical authority, reflecting their priorities and allegiances. Indeed, museum statements form a visible crack in the edifice of these institutions’ overall performances of neutrality. They echo a given museum’s interests, biases, and efforts to secure its position amid larger social and political landscapes, signaling allegiance to its funders and core constituents. Public statements show where museums stand—or, at the very least, where they want to be seen as standing.

A recent example from Germany—a country where the burden of the Nazi past has led to rigid boundaries around institutional discussions of Israel, and where public criticism of the Jewish state is often deemed unacceptable—brings this dynamic into sharp focus. In November 2024, Jewish photographer and activist Nan Goldin opened her retrospective This Will Not End Well at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin with an (un)expected intervention. She began her speech with four minutes of silence for victims in Gaza, Lebanon, and Israel, as protesters gathered outside in solidarity with Palestinians. Inside, museum staff awkwardly attempted to shield the attendees from viewing the demonstrations. Goldin broke the silence with a direct question to the audience: “Were you uncomfortable? I hope so.” Her speech drew attention to both museum’s public voice and it silences, questioning their role in ongoing conflicts.

The next day, the museum issued a statement signed by its director, Klaus Biesenbach. On the surface, it expressed commitment to freedom of expression. But it also distanced the museum from the protests and from Goldin herself, rejecting what it called “the logic of cultural boycott”, and condemning “calls for violence” and “support of terrorist organizations.” The statement wasn’t neutral—it couldn’t be. Instead, it revealed the museum’s priorities, asserting its authority, evidencing its political positioning, and reaffirming its institutional identity.

If we ask, To whom are museum statements useful?, the case described suggests that the primary beneficiary is the museum itself, first and foremost. Such statements function as public markers of social identity, revealing an institution’s political positioning and idealized self-image. The Neue Nationalgalerie’s statement appears less concerned with human suffering than with reinforcing its own authority. But this should come as no surprise: if museums are not neutral, why should their statements be?

With this short reflection, my aim is to reveal a contradiction that not only museums, but also their critics, must grapple with. When museums remain silent in the face of global atrocities, activists often demand they take a stand. Yet by insisting that museums issue public statements that take positions on specific events, do those who have long worked to de-center museums’ authority not reinforce the very power we aim to challenge?

It is a tricky question, and I do not intend to provide an answer here—first and foremost because I do not have one. Rather, my intention is to provoke consideration among those who, like myself, grapple in our work with the complexities and contradictions of museums and their role as social agents and knowledge producers. As such, I ask: Should museums take a stand on every global conflict? Sadly, the mass atrocities committed against the Palestinian people are not the only ones occurring as I write these words—and as you read them. Populations in the Amazon, Sudan, Myanmar, Iraq, and Syria, to name just a few, continue to face human rights violations and ethnic cleansing. Unless I am mistaken, I have yet to see museums making statements condemning these horrors.

And I wonder again… should they be?